Recycling Changes in Pittsburgh

By Helen Wilson

Vice-President, Squirrel Hill Historical Society

Pittsburgh officially became a city on March 18, 1816, with the

By Helen Wilson

Vice-President, Squirrel Hill Historical Society

Pittsburgh officially became a city on March 18, 1816, with the signing of incorporation papers that gave its citizens the right to govern themselves. The event probably didn’t cause much of a stir in Squirrel Hill because it didn’t belong to Pittsburgh until it was annexed in 1868. Before then it was part of rural Peebles Township, which abutted Pittsburgh to the east. In 1816, the city of Pittsburgh consisted of just the downtown area.

Pittsburgh’s incorporation created the position of mayor, and since then Pittsburgh has had 60 of them. Four have been from Squirrel Hill. Pittsburgh’s 42nd mayor was George Wilkins Guthrie, who served from 1906-1909. Sixty-eight years later, Richard S. Caliguiri became the 55th mayor of Pittsburgh, serving from 1977-1988. Sophie Masloff succeeded him and served from 1988-1994. The city’s 58th mayor, Bob O’Connor, took office in 2006.

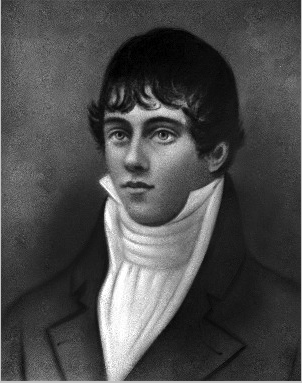

An earlier mayor also deserves mention: Magnus M. Murray, Pittsburgh’s fourth and sixth mayor, who served from 1828-30 and 1831-32. Murray didn’t live in Squirrel Hill, but his son bought land there for an estate he named Murray Hill, located where Murray Hill Avenue is today. Nearby Murray Avenue was named for Magnus Murray, because when Pittsburgh was expanding rapidly in the late 1800s, new roads were often named after prominent local historical figures, including the first four mayors of Pittsburgh.

An earlier mayor also deserves mention: Magnus M. Murray, Pittsburgh’s fourth and sixth mayor, who served from 1828-30 and 1831-32. Murray didn’t live in Squirrel Hill, but his son bought land there for an estate he named Murray Hill, located where Murray Hill Avenue is today. Nearby Murray Avenue was named for Magnus Murray, because when Pittsburgh was expanding rapidly in the late 1800s, new roads were often named after prominent local historical figures, including the first four mayors of Pittsburgh.

The theme of this issue of Squirrel Hill Magazine is the environment, and it is interesting to look at some ways Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill mayors tackled environmental issues. Because of space limitations, only a sampling of each mayors’ many achievements can be presented here. The following information was compiled with the help of Squirrel Hill researcher Wayne Bossinger.

To begin with Magnus Murray (1787-1838): Murray was elected mayor in 1828, a time when horses were the major means of transportation and houses didn’t have central heat, running water or bathrooms. Pittsburgh was just beginning to be concerned about its infrastructure, and Murray supported public improvements and humane causes, such as providing free smallpox vaccinations for the poor. Shortly after he took office, the city completed its first waterworks, located on Grant’s Hill. However, during his third term, the city council opposed a move to construct underground sewers for fear they would freeze and become useless in winter.

Squirrel Hill wasn’t annexed by Pittsburgh until 30 years after Murray’s death, and it took 68 more years for the first mayor from Squirrel Hill to be elected—George Wilkins Guthrie (1848–1917)—who was the grandson of Magnus Murray. Guthrie came into office in 1906 as a “reform” mayor, determined to eliminate the widespread government corruption that existed at the time. His accomplishments are many; a few are that he was one of the original incorporators of Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, president of Saint Margaret’s Memorial Hospital, and board member of Kingsley House Association. Guthrie is also credited with significantly reducing a typhoid epidemic that had plagued the city for over 30 years by implementing a citywide water filtration system to reduce transmission of the disease. The waterworks constructed during Magnus Murray’s term brought running water into the city but had no filtration system. Those who could afford it drank bottled water. Everyone else made do with the polluted water coming from the taps and suffered the consequences.

It wasn’t until 1977 that another mayor from Squirrel Hill took office—Richard S. Caliguiri (1931–1988), the 55th mayor, who served until 1988. At the time, the city was undergoing a painful economic downturn, with widespread factory closings, loss of corporate headquarters, soaring unemployment and huge population losses. With little control over the factors causing the downturn, Caliguiri used every tool available to rally the city. His greatest accomplishment was “Renaissance II,” an urban renewal effort that dramatically reshaped the downtown skyline and revitalized the city. He also helped create Strategy 21, a series of economic incentives that, among other things, helped convert the J&L mill site along Second Avenue into a technology center. All of the hard work paid off in February 1985 when the city was ranked as America’s #1 most livable city in Rand McNally’s Places Rated Almanac.

When Caliguiri died in office, his place was taken by Sophie Masloff (1917–2014), Pittsburgh’s 56th mayor, serving from 1988-1994. The daughter of Jewish immigrants from Romania, she was the first woman to become mayor of the city. Much of her time was spent dealing with the city’s ongoing economic problems. Costs were cut by privatizing the National Aviary, Phipps Conservatory, Pittsburgh Zoo and Schenley Park Golf Course.

The city’s 58th mayor and last (to date) from Squirrel Hill was “The People’s Mayor,” Bob O’Connor (1944–2006). O’Connor immersed himself in the local community at the grassroots level. During his frequent walks through city neighborhoods, he talked to everyone, no matter what their station in life was. They had his ear, and he acted on their concerns. One of his early initiatives was the “Redd-Up Pittsburgh” program, an effort to clean up blight. A Public Works “strike team” was set up to target specific problems, coordinating its efforts with neighborhood volunteers or other departments. Sadly, O’Connor died after just seven months in office.

Pittsburgh—and Squirrel Hill—have changed a lot since Magnus Murray’s times. Through the years, an awakening concern for the environment has brought improvements—cleaner air and water, large city parks, revitalization efforts, and reclamation of devastated industrial sites—many of which were made under the direction of Pittsburgh’s mayors from Squirrel Hill.

Anyone interested in learning more about Squirrel Hill history is invited to attend the meetings of the Squirrel Hill Historical Society, held on the second Tuesday of each month at 7:30 p.m. at the Church of the Redeemer, 5700 Forbes Ave. Go to www.squirrelhillhistory.org to view upcoming lectures and events. They are also posted in the calendar in this magazine. Please consider joining the SHHS. Membership is only $15 per year ($25 for families). There is no charge for attending the meetings.